Why Qualified People are Declining to Run for Office and How We Can Change That (with Angelia Wagner)

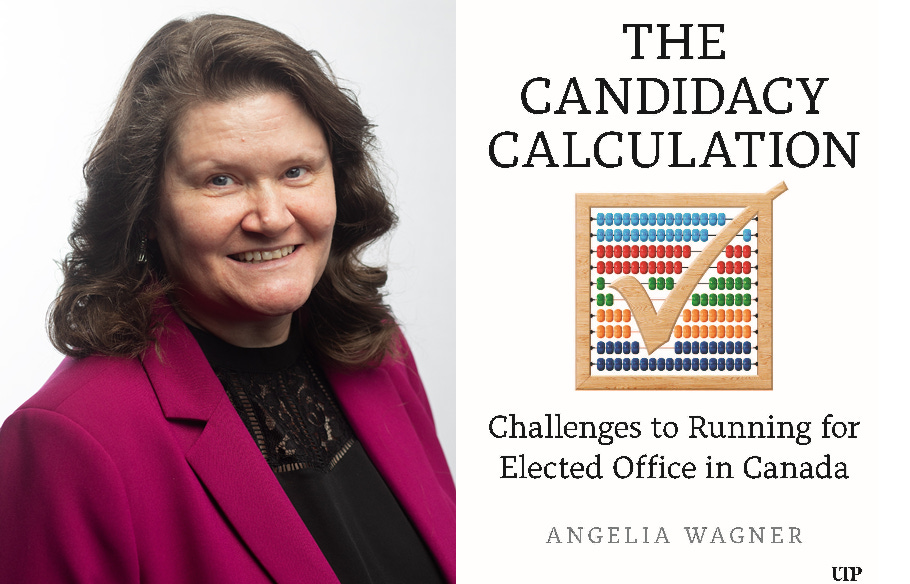

Angelia Wagner's new book, "The Candidacy Calculation" provides a crucial look into the barriers preventing people from running for office and the solutions political parties could pursue.

Today’s conversation is with Angelia Wagner, who recently published a fascinating book exploring an area of Canadian politics that has been under-researched: the thought-process that potential political candidates go through when deciding if they will run for office.

In The Candidacy Calculation (available for purchase here), she shares the findings from an extensive collection of one-on-one interviews with both past candidates and those who were qualified to run, but turned down an opportunity.

It’s a book that raises thoughtful questions on the roles of political candidates, the expectations we thrust upon them, and the environments we surround them with. I’ve often found myself questioning if there are structural changes we can make to encourage the best and brightest among us to run for office, and The Candidacy Calculation provides a strong evidence-based framework to advance that conversation.

Our chat went much longer than either of us had planned - hopefully a good sign that this book will succeed at sparking more conversations among political reformers! I’ve had to trim it down a bit below, but I encourage anyone interested in delving into the topic more to read the book!

AK: What inspired you to write about the decision-making process of candidates and potential candidates for The Candidacy Calculation? What question were you trying to answer by looking into this part of the political process?

AW: The book project was inspired by my research on how journalists cover women politicians, as well as my own experience as a newspaper journalist covering politics for many years.

My scholarly research up until 2015 was focused on the role of gender in how journalists covered politicians. My master's thesis looked at Alberta newspaper coverage of municipal candidates, and I was involved in two collaborative projects with my graduate supervisor that looked at the role of gender in how journalists covered party leadership candidates. We looked at the Wildrose Party leadership race in 2009 featuring Daniel Smith, and in a different project we looked at media depictions of candidates running to lead federal political parties over an almost 40-year period.

We did find quite distinct differences in how journalists covered women versus men, but what's really germane here for our conversation is that the gendered mediation literature, which explores the role of gender in political journalism, makes the argument that we need to care about media sexism because it might discourage other women from running for elected office in the future.

This was the argument, but nobody had really evaluated whether or not it was true. Since I started this candidacy project, one study has been published that found media sexism can depress political candidacy, but back in 2015, it was just more of a received wisdom and assumption rather than anything that had been empirically determined.

Based on my own research and, of course, my experiences as a journalist, I really wondered whether it was true that media sexism was a barrier to candidacy; because I knew that the research and my own experiences revealed it's mainly women seeking the most powerful political positions who face this media sexism—they're the greatest threat to patriarchal order and patriarchal power because they actually get to make the decisions. If you're a prime minister or president, you're the head honcho, you're the one making these decisions.

If you don't want that, as a journalist, you will use gender stereotypes and other things to discipline these women and even try to expel them from politics, to raise questions about whether or not they are the ideal political leader. But rank-and-file women candidates, the ones seeking to be a backbench MP or a regular, let's say, town councillor, aren't going to experience media sexism or won't experience it anywhere near to the same degree. If they get covered at all, they'll get the obligatory candidate profile, which is in many ways just a replication of their own bio that they might put on their own campaign website. Whatever they choose to discuss about their personal lives will be reflected in the story.

I really questioned whether media sexism was this barrier, and that got me thinking about, well, what about other assumptions are there in the candidacy literature about the gendered barriers to candidacy?

Does family responsibility still matter? The early cohorts of women seeking elected office … really did face that question of: who's taking care of your kids if you're running for office? And of course, they also were worried about that themselves. Can we combine politics and family? Because in our society, women are expected to be the primary caregivers, and so that was a very legitimate barrier to candidacy for many decades.

But an American study back in 2014 reassessed this barrier. They found that women are not necessarily being deterred from running because of family responsibilities any more so than the men. This barrier appeared to be lessening over time. Women appeared to be finding ways to deal with their caring responsibilities.

We've never really looked at family responsibilities in the contemporary candidacy scene, especially here in Canada. A lot of the candidacy literature focuses on the United States, which has its own political system. Their own political institutions, structures, rules, and norms that we don't have in the same way here in Canada.

These two examples [media sexism and family responsibilities] illustrate my thought process when it came to thinking about what's my next project.

I decided that I wanted to reassess these traditional barriers. Do they still matter? And if they do matter, in what ways do we need to nuance the conversation today in ways that maybe weren't happening in the past because we see much more variation in family forms today? And do they matter the same way for all groups of women?

Another thing that was really interesting about that one US study is it raised questions about whether we should make the assumption that family responsibilities don't limit men's political ambitions. My book research found that there are some men who choose not to run because of family responsibilities and some men who modify their political ambitions. They run for municipal office as opposed to federal or provincial office because, in a lot of small towns and villages, it's really easy to combine politics and work and family.

I also wondered: what aren't we paying attention to? What other factors are influencing candidacy that we're not talking about? Are there new barriers that have popped up that we need to pay attention to? And are there barriers that we've overlooked? How are they playing out?

The point of doing interviews with candidates and eligibles was to give them the opportunity to really generate those insights. When you do a survey and you build that questionnaire, you are choosing the answers, because you're limiting them. You're giving them a range of answers, and then maybe an ‘other’ category to try to capture all of these other ones, but in many ways, those surveys predetermine which factors you're going to look at. I wanted things to be much more open-ended. I wanted the people who might one day run for elected office and those who actually already had to tell me what the factors were that might have kept them or did keep them running for elected office. And that proved to be really quite fruitful.

So, if there is that big question that was driving this project, it was to really understand, to reassess those traditional barriers and to identify and understand any new or overlooked barriers to candidacy in a much more holistic fashion.

AK: You explored a number of potential obstacles for those considering running for office in your book and your interviews. What surprised you the most compared to your expectations coming into the interview process?

What surprised me were those overlooked and emerging factors. When I first started this research back in 2015, online harassment of politicians was just emerging as an issue, as were social media scandals. Activists in the Global South had long been attentive to violence against women in politics, which includes online harassment of politicians. They've been attentive to those kinds of issues going back to the 1990s, and would add these other factors [related to digital media] as they continued to explore the issue. But activists and journalists in the Global North only really started to clue in around the 2010s when online harassment became a big issue here.

So, the literature didn't prepare me for certain kinds of issues that emerged during these interviews. I developed my interview questions based on what the literature had already been talking about and I pre-tested the survey questions with a few people, a few partisans, if you will. That's where I was really surprised to learn about the importance of social media scandals for young people. Because young people are these digital natives, they've basically lived their lives online going back to when they were kids. It doesn't seem like a long time from my perspective, you know, five or 10 years ago, but for them, that's their adolescence. They were really deeply worried about how things that they might have posted online five or ten years earlier, when social media really started to first emerge, could come back and haunt them.

This was around the time where we really started to see opposition research generate these social media scandals where candidates were being forced to resign or being turfed by political parties because of a post that they did five to 10 years ago that someone might've found problematic. Maybe they've said something that went against the party platform or they're saying something that isn't socially acceptable. They're still trying to figure out what they believe in when they're teenagers, and I would argue it probably even takes a long time as adults to fully understand what you believe in, but there isn't this acceptance that your views can change over time. People will still hold you accountable for what you said 10 years ago, even though your thinking might have changed.

So young people were really worried about that. And that led me to add a question to the interviews and ask people: are you worried about social media scandals, that your candidacy could be torpedoed because of something that was posted online? I even interviewed a couple of people who had suffered from social media scandals. In one case, it definitely did derail their candidacy, but it also had impact in other ways on their life.

Online harassment didn't emerge as an issue to study until I started interviewing for the actual project. I interviewed a woman here in Alberta who had run for municipal office, and I went into the interview asking my usual questions, but she immediately started talking about online harassment. And it was like she couldn't talk about anything else until we addressed that. I used my journalism experience to pivot and just said, basically, tell me about this.

That's when I was really clued into the ways in which online harassment could act as a barrier for women in particular. There wasn't literature on this topic back in 2015, 2016, 2017. It's only been in the last few years that we're really starting to see that research come out and explain more of what's going on, so that was something I was not anticipating. It's this new barrier as a result of digital technologies and social media.

The other thing that really surprised me was just how much public scrutiny in general was serving as this barrier to candidacy. Journalists and voters have always monitored what politicians say and do. But historically, it's been more about their political activities and their policy ideas. Over time, that's changed to where we're starting to evaluate their personal lives. For some voters it matters more than for other voters, but the advent of digital media has really intensified that scrutiny.

It's made it possible for voters to very quickly, swiftly, and extensively critique politicians and even harass them. Rape and death threats, these kinds of things. And it was LGBTQ+ people in particular who were saying ‘public scrutiny is the reason why I won't run.’ They were the only ones who actually, definitively said ‘this barrier is going to keep me from running.’ Other people, we generally talked about the ways in which they viewed family responsibilities or campaign fundraising as challenges, but queer people were saying, ‘I'm not gonna run because of this.’

What I came to realize by analyzing all of their responses is that they didn't want to subject themselves to the moral regulation that often accompanies public scrutiny today. They've already suffered a lot of public assessment in their own lives around their sexual and gender identities. They don't want to experience it on a much larger scale.

These are just a few of the things that really surprised me, but that was the whole point of doing the research project. I wanted to be surprised. I wanted to find out all of the factors that go into that decision-making process on whether or not to run. And one thing that I do want to get across here in the interview is that when I'm exploring the reasons why people are choosing not to run, I'm in no way blaming them for not running. I don't want anyone to think that this is an individual problem that's got to be resolved by individuals.

People make very rational calculations about why they will or will not run for elected office that reflects their own assessment of their personal circumstances and the political opportunity structure. Is politics something that they really want to go into? It's important that we think about it that way, that the interviews are about trying to understand how they view it so that we can generate insights that can point to structural and institutional reforms that can make politics more welcoming for a more diverse group of people.

AK: Yeah, I think for me one of the really important things about this book is that shifting of the focus to talk about this more structurally. I think in Ottawa often the conversation around recruiting candidates is on a case-by-case basis. What can we do to get this person to run for us? It's not a conversation of ‘we need to create an environment that makes it so that these people actually want to run so that different people get approached and different people get this opportunity and they feel comfortable and supported.’ Your book does a good job of looking at this more holistically and figuring out those common factors, including social media.

AW: Well, the thing with social media, and I've told my students this, is that it now makes the water-cooler conversations publicly available. The whispering campaigns are now something that we can all hear. A lot of these conversations that probably were taking place privately in the past amongst people at work or at the café or in their own home are now being aired on social media.

Another thing that I think young people in particular don't seem to fully understand about social media is that what you say or post online is a form of speech. And it's a form of political talk, right? I say this because the young people I interviewed often believed that these social media scandals are only going to be a temporary issue, that we're only going to care about this maybe for a couple of decades until such time as their generation becomes the majority of the electorate. They presume that other people their age will just come to understand that there's certain things that you've done online that you should be forgiven for, that you didn't experience all of this privately, as it were. It's all out there now.

But as I say in the book, I think that fundamentally misunderstands the way in which journalists and others view what you say online as a form of political talk, that it is a record of your political speech. We do see politicians being evaluated for what they said 10, 20, 30 years ago. Think about discussion around Donald Trump, all the receipts that people bring up when he says one thing today and they bring up what he said 10 years ago, 20 years ago and the ways in which they might be either consistent or contradict one another.

So, I worry about the potential for social media scandals to really limit the candidacy of a lot of different types of young people. Not just young people in general, but perhaps specific types of young people, the activists, the ones who really need to promote a particular issue. We haven't done the research yet, and I really couldn't get at this in my book, but I wonder how much of an intersectional impact that social media scandals have, but also the candidate vetting that takes place now because of the potential for social media scandals. What kind of impact is that having on who gets to run?

Maybe people who are Indigenous or racialized or feminist are not making it through the candidate vetting process because of something that they said online, even if they try to scrub it, because the internet seems to be forever.

AK: I was struck by a phrase you used in the section about family obstacles: “Voters want politicians to be parents in spirit, but not in practice.” Can you talk a bit about what led interview subjects to express this perspective and why that discouraged participation among some?

AW: Well, that statement really reflects a tension that I saw in how respondents talked about family responsibilities, as well as what I've seen in the academic literature around politics and parenthood. Voters really want politicians to be parents because they believe that personal experience will enable them to develop better public policy to help families. They want politicians to understand what they are going through, but the all-consuming nature of politics and the expectations that voters have of what politicians should do with their time really doesn't leave a lot of time for politicians to be involved parents, at least while they're in politics.

I'm sure you've seen this on the Hill. One of my participants described it as the Ottawa bubble where you are so deeply immersed in politics, policymaking, and the like that any kind of intrusion can seem almost violent in a way. That having to worry about something else is just, it's too shocking. It's just too much to handle, right? And if you consider how big Canada is, some people have to fly from one end of the country to the other to be able to go back to their constituencies [giving them even less time with their families].

I know I'm preaching a bit to the choir here, considering your audience, but politicians are spending much of their day, Monday to Thursday, maybe Friday, really involved in what's going on in Ottawa. Then they have to fly back to their constituencies and be involved there because voters expect to see them in the constituency. They need to be active. As soon as they arrive, they are going to one community event after another. If they're in a small riding, like a physically small riding, it's easy to go to several events because they're probably all within a block of each other. But if you're going to one of the northern ridings that are bigger than some European countries, getting around from one event to the next is very time consuming.

There isn't a lot of time for them to spend with their families, unless they're lucky enough to have an Ottawa riding where they could actually go home and have dinner, where their life and politics could work better together. But that's not the experience of most MPs, if you think about it that way.

There's also expectations on the part of parties that their members should always be available for whatever the party needs them to do. Let's say that is to vote in a legislative vote. Because of how things have happened historically, you have to vote in person. I was told about how one politician couldn't go to their kid's high school graduation because they had to vote. This is why we need to talk about reforms like remote voting that would allow them on an iPad or tablet to just say, ‘I'm voting in favor of this,’ and then get back to their kid's high school graduation.

I don't think it's unreasonable for parent politicians to want to be able to attend a high school graduation or their kid's wedding. They're not necessarily asking to be there every single day, you know, for eight hours a day with their family, but they want to be able to attend some of those key events, because their kid's going to remember that they weren't there.

This is what I'm talking about in terms of that tension, that politics doesn't allow parent politicians to really be parents while they're in elected office. And that's why we've seen feminist scholars in particular really call for institutional reforms, why they want to see remote voting or hybrid voting, why they want to see daycares being built at legislatures. Why they want working hours to be more amenable to parents being able to go home and cook for their kids. Where we actually look at the work culture on parliament, because one thing that often gets overlooked by a lot of voters and others is that legislatures are workplaces.

We forget that politicians are workers, and they should have certain kind of rights that other workplaces do. There's really a lot of institutional reform that needs to take place to make it possible for politicians to combine politics and family so they can be parents in practice, even while they're in office, but that's hard for them to do.

There's an example here in Alberta. Former Alberta premier Alison Redford faced a lot of criticism when she would take her daughter with her to events around the province because that would necessitate taxpayers paying for her flights and whatever other expenses. I personally never had a problem with it because I understood that it would be difficult for her to combine politics and parenthood and I thought that that was a neat solution—that her daughter would be able to come with her and spend time with her but also understand what her mother does better. I didn't personally have a problem with it, but If critics want to get rid of you, they will find a way to do it in Alberta.

What I'm trying to say is that politicians, but especially women politicians, face a lot of criticism if they try to find ways to combine family and politics. It can make them more vulnerable to critiques, even from people who would otherwise claim to be about family values.

What was really interesting is that it was female eligibles who really identified the structural factors that make family and politics incompatible right now, whereas the people who actually held elected office thought it was up to the individual to try to find a way to figure it out, and specifically their spouses. What we're really seeing here is how the ways in which white wealthy men have historically lived their lives has structured how political institutions do their work. Because these men have a spouse at home taking care of the kids, a wife at home, they're free to devote themselves completely to politics. There's no need to worry about a work-life balance because they don't need it—other people are taking care of their domestic responsibilities for them.

This is what feminist scholars and these female eligibles are really critiquing. They want to see the system reformed so that it takes into account the different family forms, the different ways in which people do or don't engage in caring responsibilities.

Another thing that came up is that when we think of family responsibilities, the literature tends to think about children. But we also need to think about elderly parents, sick family members, and those caring responsibilities also fall to women. And so we need to think a little bit more broadly about family than perhaps we're used to in Western societies.

AK: One factor that is discussed a lot on Parliament Hill is MP independence. Some people say more potential candidates would want to run for office if there was some leniency for MPs to vote against their party on occasion or pursue their own projects without centralized oversight. Based on your research, do you think this sort of concession would actually result in more people running for office?

AW: Well, many people who run for elected office do it because they want to have an impact on public policy, either in general or on a particular issue. I think if we did see more independence or influence by regular MPs that it would lead to greater satisfaction in office, and that in turn might communicate to would-be candidates that they could achieve some of their goals in elected office if they were to run.

One of the problems that we have in Canada is that we have the strictest party discipline out of all parliamentary systems. Even in the UK, where we get our system from, has much looser party discipline than we do. There's all sorts of reasons why it's easier for them. I think because of how we select our party leaders here, party leaders much greater power in our system. In the UK, it's the parliamentary caucus that determines who the leader is, so the party leader actually has to make sure that members of caucus are happy, that they are having the kind of influence that they want.

In Canada, we treat leadership races more as general elections where all you need to do is buy a membership and you can vote, which means the party leader is not beholden to their own caucus but rather to the party membership. It's easy for them to wiggle out of certain caucus expectations because you could always say, well, I'm appealing to this part of the base or that part of the base. And so I think that's where we come to how structural or institutional factors can really influence candidacy.

I did talk to people who would like to run for elected office, would like the opportunity to influence public policy, but they don't really see the opportunity. They get a lot more satisfaction out of being involved in social movement activities or with other kinds of organizations that allow them to have the impact on society, either in general or in relation to whatever kind of issues really animate them. So, I do think we are losing out on individuals who could be quite dynamic in terms of policymaking.

The challenge here is that a lot of the people who might be self-selecting out of politics could be the mavericks that our system doesn't seem to really like, because they are more likely to disagree with the party. They're more comfortable saying ‘why can't I support the Conservative policy on this issue that I agree with instead of our Liberal Party policy that I don’t think quite does the job?’

There's this desire from these folks to be more like American politicians. The U.S. has a candidate-centered political system where individual candidates and elected politicians really can drive policy in ways that far less possible in our party-centered system. I think there's a lot of tension going on there that will make it uncomfortable for the party leadership to loosen the strings, if you will, on them. But I do like the fact that the parties are having that conversation because it does speak to a larger kind of dissatisfaction for the backbenchers.

I think that's why committee work becomes so important to a lot of them. It becomes a way in which they can influence policy. But, unfortunately, party politics has also taken over the committees, and it's really become more intensely partisan than maybe it had been in the past.

I do think it's important to have that conversation about party discipline in particular, but we also need to talk about ideological alignment. Maybe this isn't as important for people on the Hill, because you're going to want to recruit people who agree with the party. But I found that there's a lot of individuals who are really interested, really want to get involved in politics, but are choosing not to run because they can't find a political party that they can fully support because of that party discipline. They know they need to support at least 75% of the party platform before they're willing to subject themselves to that party discipline.

What I found when I talked to racialized people in particular is they're not willing to do that because in many ways the parties don't advocate for policies that really help their own communities. And racialized candidates, they don't want to be the token candidate who helps the party check off these diversity boxes without that also translating into substantive representation. They're not interested in just being there so the party can to say, ‘oh, we've achieved descriptive representation.’ They need it to translate into substantive representation.

The fact that these white wealthy men have dominated our politics historically and still today means that a lot of policy still benefits that group in particular, and other people aren't seeing policy being reflected in what they're doing. If political parties want to think about what they can do to make politics more welcoming, I think they really need to reevaluate their own policies and actually, substantively respond to the needs and interests of different groups, which is extremely challenging when you have competing interests. But it is something that they have to think about if they want to be able to recruit those really talented people. Talented people are not going to want to just be window dressing.

AK: What other concessions or changes might political parties have to make if they are serious about creating an environment that will attract more people to run for office?

AW: Well, I talked about the importance of the party platform actually taking the needs and interests of different social groups seriously, although I do recognize that is challenging.

Political parties can also change their own internal culture. One idea, for example, would be to provide childcare at party events so that parents can bring their kids with them if need be. Also making sure that they protect time in politicians' schedules: okay, you absolutely get to go to your child's wedding, we will push for things like remote voting.

COVID really gave parliament an opportunity to experiment with digital technologies. Take advantage of that to find ways to make legislative business easier to do. Is there a way that you can use facial recognition so that when they sign into their iPad, it takes a picture or something so they can actually vote before they go and attend their kid's wedding? They can quickly vote and then get back to the festivities. Find a way to build into the workplace structure, schedule — however you want to put it — ways for them to be better parents and to be involved in their kid's life, especially in the big events.

I would also encourage them to also think about the mental and physical health of their candidates and politicians. We haven't touched on that particular chapter of the book. There were a number of candidates who just voluntarily addressed that issue, and it's one that we're not talking about. Politics can be physically difficult on people. Think about the fact that Barack Obama went prematurely gray within four years of assuming the U.S. presidency. I've had people tell me off the record that it encourages drinking. They self-medicate to deal with the pressures of politics. If they already had that issue to start with, it might only make it worse.

The party should think about ways in which they can encourage a healthy diet. I understand that Justin Trudeau encouraged his members to stay physically fit and to follow a good diet, which is really hard when they're going from one event to the next. I don't know if this is a legitimate expense for politicians, but maybe allow them to be able to pay for groceries or some of these meal services or whatever where they have something that they can take with them and eat healthy while they're going from one event to the next, rather than just taking a chocolate chip cookie or whatever might be on the refreshments table at an event.

I understand Jack Layton was very protective of his workout time when he was on the Hill. Find ways to actually build that in and respect that time. I would encourage parties to think about and reflect on their internal culture and ask: are we creating an environment where politicians can take care of their mental and physical health, where they can be there for the big events in their families' lives, where they can take care of caring responsibilities while their children are young? Think about how hard it's been for women to be able to bring their newborns into the legislative chambers in order to breastfeed.

There are also other ways in which parties can signal exclusion or political institutions can also signal exclusion. And that's through rules, for example, around how you dress. Men are expected to wear a business suit, but that's a European style of dress. Other cultures have other kinds of styles of ‘business’ dress that aren't allowed in the chambers. The legislature has also faced challenges in terms of first allowing and then providing translation services for Indigenous members who want to speak their own language on their own lands.

One thing that I would recommend parties do in particular is go and look at Sarah Child's report called The Good Parliament that was published in 2016. She conducted a very thorough examination of the issues in the British parliament. Now, some of them are very specific to the British context, but there's others there that I think could be relevant for Canada that they might want to look at and institute in order to make the institution and the parties more responsive to different groups.

She focuses specifically on gender, but I'm sure through focus groups with your own members that you could find other ways in which other social groups could recommend changes that could be made to make politics more accommodating of different groups. I think there's an untapped resource there.

AK: I really liked that your book felt like a conversation starter, and I hope it inspires people in politics to think more structurally about how we can remove barriers preventing capable people from pursuing elected office. What’s the next step if parties or researchers want to take your work and expand on it to find solutions?

AW: Well, if people are interested in the book, the final chapter revolves around providing ideas on what could be done to address some of the different issues. One of the things that I try to do is to think about the practical implications of the research. I remember going to a two-day workshop or conference at McGill University, where I first started this research, and people with an agency that organizes elections would listen very politely to what all the scholars were talking about in terms of voting and all that. Then, when it was their turn to ask a question, they basically asked, ‘well, what do we do with this information?’

That got me thinking about what would I do with my own research? The final chapter of the book is designed to try to start that conversation, to highlight some of the issues and ideas that people generated in the interviews, but also to talk about what the literature more broadly is trying to do. That's the beautiful thing about feminist research in particular: it's not just interested in understanding the problem, it wants to actually fix the problem. Because feminism is a political project as much as it is an academic one. That's what I've tried to do here.

One of the things that I think we do need to think more carefully about is to really take that closer look at how political institutions operate at all three levels of government. Each legislative body is going to have its own particular set of challenges. I think it would be really useful if we had someone do that critical evaluation of Canada's House of Commons that Sarah Childs did for the British parliament and really try to identify actual practical solutions, keeping in mind that we are a way bigger country than the UK. We've got issues of geographical size that really influence the ability to do certain things to find a work-life balance in politics.

One thing that I want to take the next step and actually do a survey to find out the extent to which these factors are actual barriers. This book has been about understanding why they're barriers and how they might be barriers for different types of people. But I can't actually tell you that 20% of white women are choosing not to run until their children are of high-school age. I don't know that. And as far as I know, no one's done the kind of survey in Canada where they systematically try to examine all of these barriers and how much they actually matter, both overall and for specific groups.

That's where I want to take my research next, because I want to be able to give that definitive answer, give us that overview, so we understand the scope of the problem. One of the things that I see with campaign schools is a lot of it is naturally focused on the election campaign itself, but they're not addressing those other factors that we've been talking about that influence whether or not people actually take the candidate campaign training, whether they actually put themselves forward. If they do, they might decide after taking the campaign training that it's not for me because they're not actually addressing the issues that are of concern to me and how I can deal with them.

I've done other research that looks at the City of Edmonton’s Opening the Potential program that was designed to encourage more women to run for municipal politics. Out of everyone who took the course over the three years they ran it, I was told that only something like one person stepped forward to run for office. Some of the women that I interviewed as part of this book, the campaign school made them realize just how much work actually goes into being a candidate and that they can't just quickly turn it around and run. Other people were frustrated that the system just seems to say, ‘you figure it out,’ because that in particular was something that I heard from racialized women and immigrant women. They would get these guest speakers at the campaign training school who would basically say it was up to them to figure out how to balance politics and family, and that answer didn’t fly for a lot of these women.

I want to be able to understand the extent to which these issues matter. We need to rewrite survey questionnaires to consider the broader range of factors that are at play. For example, is online harassment actually the barrier to candidacy that a lot of feminist scholars and activists are scared that it is? We don't know. I think we need to take more seriously the need to evaluate the variety of factors that matter to candidacy and to take that comprehensive look, because right now we're just guessing. We think it matters because, anecdotally, we're being told this by a number of different people, but the next step is to really understand that quantitatively.